[Editor's note: As a matter of respect, Dancer's Turn's style calls for the initial use of an artist's full name with subsequent references using the surname only. iele paloumpis, as a survivor of domestic abuse, notes that, "self-naming has been an important part of my journey, as a survivor and as a trans person." On their request, iele paloumpis will be referred to by their full name instead of the surname, "paloumpis," as a compromise between iele paloumpis and Dancer's Turn that will respect both the artist and the publication's style.]iele paloumpis is many things–among them, a witch like me.

I knew I’d want to talk to iele paloumpis–a dance artist identifying as trans/queer–when I heard that their workshop in neopagan ritual,

Witchcraft: a corporeal practice, would be hosted by New York Live Arts as part of its Shared Practice series this spring. I missed my chance to attend but wanted to hear all about it.

“We created a bodily circle and consumed salt and sage, taking this into our bodies to create that safer, sacred space together,” iele paloumpis told me. “Instead of burning herbs, we made herbal oil infusions for bodily healing.

“I base it on the lunar calendar. What’s happening with the moon, what sign it’s in, what’s happening with the planets astrologically guide what sort of ritual we will do and what sort of meditations we will have–if it’s about welcoming things and bringing energy into our bodies, or if it’s about expelling energy outward in different areas of our lives. The class is ever-evolving. That keeps it exciting for me.

“During the Shared Practice, Mercury was in retrograde, and the Moon was between Taurus and Gemini, void of course. A lot of witches believe, ‘Don’t do anything during Void of Course! And don’t do anything during Mercury in retrograde!’ But Mercury in retrograde--those interruptions that we experience--are telling us to slow down, telling us to go back to self-reflection and think about past experiences, our histories. Void of Course, similarly, is good for meditation, therapeutic things, in between worlds.

“We did a walking/moving improvisational meditation starting at one side of the room which we said was ‘Birth.’ When you got to the other side of the room, you were in the present moment. You were thinking about–and moving–your history and bringing it into the present.”

|

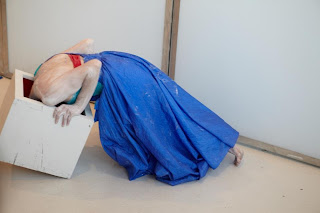

iele paloumpis in improv

(photo by JJ Tiziou) |

For better or worse, our histories continuously permeate our present realities. iele paloumpis lives with a history that both challenges and stimulates the artist, educator and advocate they have become.

“When I was four,” they say, “I got into a major accident: a shopping cart fell on my leg, breaking my femur and cracking a growth plate in my hip–a spiral fracture, one of the worst fractures.”

The child should not have been moved, but a worried adult, not waiting for medical assistance, picked iele paloumpis up and ran through the store.

“The bone twisted, facing the wrong way, and there was danger of my leg never growing again,” says the dancer. “They had to fly in a special doctor who could set baby bones, and he did a good job. I was in a body cast for four months, from the middle of my chest, over both hips and then down to the tips of my toes. I don’t remember a lot from that time, but it was one of my first memories of a lot of pain.”

During their convalescence in the cast, their muscles atrophied. When the cast came off, they would need physical therapy to regain strength. On advice from their doctor, their mother enrolled them in dance classes–mostly tap with the Chicago Human Rhythm Project--and did volunteer work at the studio to defray the cost of attendance.

iele paloumpis continued to enjoy dance, never once considering it as a potential profession. Their future choice of a college, though, would tip them in that direction when, with a primary interest in literature and writing, they selected Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia.

*****

The young iele paloumpis had grown up just outside of Chicago in difficult circumstances, raised by a mother who suffered epileptic seizures and a conservative, Greek Orthodox father who was frequently abusive.

“My parents finally divorced when I was in high school," iele paloumpis recalled. "But at the time, there was this horrific law: if you’re going through a divorce, the first person who leaves the household gives up their rights to whatever monetary gains they would have gotten from the household. Since my family didn’t have a lot of money, paying lawyers fees almost caused the house to go up for foreclosure. Neither of my parents could afford to leave the house. It escalated things, and it got really violent.”

Their mother had placed some of the settlement funds from iele paloumpis’s accident in a CD. To help iele paloumpis escape the unsafe household, their mother advised taking half of that money to buy a car to live in. iele paloumpis used the remainder for food and gas for getting to school and work. Friends sometimes allowed the youngster to couch-hop, a chancy situation. Finally, the mother of a fellow dance student, a devout Baptist from an affluent family, opened up her home. She also guided them through the process of applying to colleges, taking advantage of resources available to students unable to depend upon parents for support. iele paloumpis would be the first in their family to attend college.

At the time, iele paloumpis’s mother–with her epilepsy advancing to a dangerous state, with numerous seizures per day--faced emergency, life-saving brain surgery. Within days after the surgery, iele paloumpis headed to Virginia and college with the gift of a Bible and a plane ticket likely paid for by their friend's mother.

Thanks to Donna Faye Burchfield, Hollins University had launched its first baccalaureate and graduate programs in dance in collaboration with the world-renowned American Dance Festival where Burchfield also served as dean. At Hollins, iele paloumpis was surrounded by exciting up-and-coming dance artists.

It didn’t take long for dance to work its magic. iele paloumpis attended a dance festival at Hollins where, oddly and wonderfully, things didn’t quite go as planned.

“A big windstorm cut the electrical power right before the show was supposed to start. No one could see anything. Donna Faye rallied everyone around. They got candles, they got flashlights, they got everything they could and put them on the stage. Chris Lancaster, the accompanist, got out his cello, and Donna Faye called forth Isabel Lewis and all these other people to improvise–the most amazing thing I had ever seen. There was spoken word poetry, too. And then, at this pinnacle moment, the lights came back on–and they did the show!

“I was like, ‘I have to know what this is!’ I had never experienced dance like that in my life!”

So iele paloumpis approached Burchfield. Although their training had been very different from the offerings at Hollins, they started taking dance classes and ended up with with a double major in writing and dance.

|

| photo by Adrien Weibgen |

At Hollins, a women’s college, iele paloumpis also began to question gender identity.

“I was very much identifying as a woman--and I still wholeheartedly identify as a feminist, even though I don’t identify solely as a woman now. But there was always something that didn’t resonate for me around the language about being a woman. It didn’t quite feel right. And I don't mean oppressive/homogenizing language that is often used to describe women. No one identifies with that!

"Moving away from conceptualizing myself as solely female has been a complicated journey, but there's something about how I related to my own body. It was visceral and nonverbal, and so it’s hard to put words to.

“There are many different ways to identify as trans. Some people identify within the binary, being assigned a certain gender and then crossing over–male to female, female to male--to better reflect their gender identity. Personally, a binary expression of gender is not how I identify. I feel that there are masculine and feminine forces within my body, and I think to a certain extent that’s true for everyone, but it’s also how I relate to my anatomy. No one knows my body better than I do, just as no one knows your body better than you do, and so on. Ultimately, it's about self-determination and supporting each other within that.

“Graduating from Hollins and moving to Philadelphia--which has a very strong transgender/genderqueer community--was the first time that I was exposed to trans-ness in terms of fluidity of gender, more expansiveness, which was what I identified with and how I came into my own gender identity.”

Using the pronoun “they”–instead of “she” or “he”--came to express that breadth, depth and fluidity of gender.

Defining self for self, and throwing off oppression, had long since led iele paloumpis away from their father's Greek Orthodox religion, as well as the born-again Christianity of their friend's Baptist household. And yet, the symbolic, ornate ceremonies of the Orthodox tradition seem to have foreshadowed the rituals they create in both witchcraft and dance. Both pursuits represent a deep call to healing from trauma.

“It came back to healing, the layers of getting in touch with my body through dance with my history of abuse and violence, and being around women who had experienced violence, too. That was a very strong conversation happening at Hollins, and feminism was a part of that. I was thinking about my body and all bodies in a way that’s complex and about things not immediately visible.

“The idea of invisible disabilities is an odd thing. It’s invisible some of the time...until it’s not. My mother could often walk about the world, and no one would know that she had epilepsy until she was seizing or there was some other indicator. That, and the ableism that she experienced and that was constantly causing her to be between jobs, was always very present in my mind.

“Very young, I innately had the sense of injustice around my family’s class background and how that related to my mother’s disability and the domestic violence, and how that connected to our bodies. As I got older, I became more and more politicized around disability justice, connected to my mother’s struggle.”

This concern for justice extends to iele paloumpis’s work as an educator for the Arts and Literacy Program of the Coalition for Hispanic Family Services, providing consistency and safe space for young people from low-income families.

*****

“Within the past two years, I’ve been experiencing various physical ailments that have not been able to be diagnosed by doctors until recently," iele paloumpis says. "I’ve been navigating those things in my own body. I have an impairment that causes double vision.”

A cranial nerve lesion causes the double vision, a fairly rare condition that falls outside the expertise of most ophthalmologists and neurologists. They now consult with neuro-ophthalmologists specializing in double vision. Corrective lenses help somewhat; physical therapy, so far, has not been as effective as it might be in children with the disorder.

“The condition is very disorienting and causes a lot of dizziness. It’s weird: Your body adjusts over time; your body wants to orient itself. I realized I was compensating in all these different ways: I’m much more of an auditory learner now than a visual learner. Then it was, like, ‘Oh, I haven’t been reading for like a year.’ I can pick out words here and there, but I can’t read paragraphs. Since writing has always influenced my dancemaking, that has been difficult. There’s audio software that can read things aloud and magnification on my computer, but they’re imperfect programs for sure, and it restricts me to only reading things online.”

They avoid the typical bestseller audio books: “I don’t need more of that in my brain!”

Motion heightens their dizziness and queasiness.

“When I’m moving and dancing, it’s way too much, and that inhibited me to large degree when I had this wonderful studio residence at New York Live Arts over the past year. A lot of it was working with a sense of limitation and a feeling of not being able to trust my body in the way that I had once known it.

“At the same time, I was thinking about how to integrate this new thing that’s happening in my body–and not in a way steeped in internalized ableism. This is my body. This is what I’m going through right now. How can I embrace that? How can I integrate that into my dancing and my life?"

|

Shadows of iele paloumpis at left and Jung-Eun Kim (aka J.E. Kim) at right

in Keening at New York Live Arts

(photo by Joanna Groom) |

“Last year, as I was working with J.E. Kim and Joanna Groom, my roommate at the time, I started thinking about orientation through sound," iele paloumpis said. "I found singing to be really calming. Joanna taught us how to use our voices, and it became a kind of meditation and spiritual practice to sing together. There’s subtle movement–your vocal cords, your breath–but not the topsy-turvy feeling that I get when I’m doing large movements.

“I had this deep desire to map out the space. I didn’t feel that I could see it anymore, that I could feel it anymore. Part of J.E.’s role was her ability to do that. The locomotion and directionality of her movement was about outlining the perimeter of the room. At New York Live Arts, although it was still very frontal–and part of that was for me to not be further disoriented--we turned the orientation so that, for the audience, it was from a corner vantage point.”

The disorientation, therefore, was placed on the viewers.

“For me, I was feeling the dizziness within my body, going there, doing some deep work around violence."

|

Three scenes from my mother keening

(photo courtesy of Arts and Literacy) |

This season, iele paloumpis will be further developing their work through a Brooklyn Arts Exchange (BAX) Space Grant. So, it’s onward, no matter what.

“The queasiness has made me not want to dance, but what my doctor has given me, recently, is the ability to patch one of my eyes, allowing for singular vision. It messes with depth perception, and I have no peripheral vision. I have to rely more on sound or craning my neck. I’ve been trying that out, and it’s actually been very freeing. I’m able to dance in ways that make my body feel good again. It’s a new form of navigation–both familiar and new–which is exciting!”

For a dance artist often improvising with others, could this be a challenge?

“I was very visual before in my understanding of the world around me. So that includes the way in which I watch work, how I come to understand it. I’ve been putting myself in my work a lot more recently because, despite all the physical difficulties, it has become less about watching the work and more about the experiencing of it. It’s been important for me to be inside of it. I know less about what it looks like but maybe more about what it feels like. For me, that’s very linked to improvisation.”

*****

iele paloumpis’s background as a survivor of adversity also guides how they view

the struggles faced by dance and dancers in an often uncomprehending and dismissive society.

“The only place I want to be is New York City because I have so many amazing people here, part of our dance community, that are deep friends. When the money goes away, it’s not like when I was in Chicago, when I’m not going to have a place to go. There are couches that I can still crash on here. When I first moved here, I wasn’t able to make the rent, and I was facing eviction and didn’t have the safety net. I know a lot of dancers who are on food stamps in order to survive and make their work, but I don’t know a lot who have contended with potential eviction and homelessness. So it’s hard to have a conversation with dancers around poverty."

"Within the last year, my class status has shifted quite a lot," iele paloumpis says. "I went from housing court to moving around a lot, collecting unemployment then luckily getting a steady teaching job--with health insurance!--and newly living with my partner and their sister who are from an upper-middle class background. It's very surreal. I'm coming to understand the idea of a 'safety net' in my chosen family.

"But, at the same time, my mom just got another pink slip while her current husband is laid up due to a work-related injury. I hope to one day be in a place where I can be her safety net. My mom loves dance, but she's never seen me perform in my adult life because travel costs are too high. We only see each other every three years or so."

Life experiences such as this make it impossible for this artist to be oblivious of social realities outside of the world of dance.

“For me, I think it’s important to think about accessibility, and I think that our dance community can keep itself very insular–you know, like the same people going to all the shows. The language we use is often very academic and sometimes inaccessible to others.

“We often will complain, ‘Why isn’t dance being seen? Why isn’t it considered important?’ Part of that is our own cycle of not branching out further, not thinking about accessibility.”

In fact, iele paloumpis says, the availability of dance as a healing and spiritual force becomes limited to the few. That’s one reason they remain dedicated to their work as an educator in underserved communities.

“I want to extend that to others. Those of us who do have safety nets, let’s do more and extend that conversation outward: What it means to be broke for a while because you’re not getting income as opposed to what it means to be in poverty. Of course, I think that, for most dancers, there isn’t a lack of interest in doing that. There’s a feeling of being stuck in the

how of it because of a general lack of resources. But, as a community, we could work harder to extend outward.

“I think people are worried about ‘simplifying’ dance, because we’ve really worked to make it this thing that’s recognized in an academic setting. There’s this real drive to not let go of dance being an intellectual pursuit. But we’ve gone too far in that direction.”

*****

Witches learn early that words have limitations, but the right words-- combined with imagery, gesture and other sensory phenomena--can empower. By claiming the word “witchcraft”–which, they admit, is not taken seriously by a lot of people, iele paloumpis also lays claim to a history and feminist analysis of the oppression of women and pagan healers under patriarchal religion.

A rebellious thirteen-year-old iele paloumpis--influenced by their mother’s interest in witchcraft and psychic dreams, as well as by an idolized cousin, who was a survivor and healer–began to explore neopaganism. When iele paloumpis’s mother slipped a Tarot deck–the teenager’s first–into an Easter gift basket, their father grew angry.

“Him hating it made me love them all the more. It was a special gift that allowed for that sense of healing that I was needing. I still have that deck; it’s the only one I use."

Years later, while iele paloumpis was studying at Hollins, their cousin died from a drug overdose. Sara, who was more like an older sister to iele paloumpis, had struggled with addiction throughout the latter part of her life.

"Sara's body was found in a dumpster, and the coroner told our family that she would have likely lived had she been taken to the hospital. There was no further investigation into Sara's case. She and whoever disposed of her body were just chalked up as 'junkies.' And my world shattered. It is still incomprehensible to me--these acts of violence and people's indifference to suffering."

iele paloumpis found comfort in re-connecting to Tarot as a spiritual practice, learning what they could through reading, the Internet and just “acts of doing.”

“Doing ritual, more and more, gave me deeper knowledge, intuitive knowledge. It allowed me to feel connected to Sara and my ancestors. It's been life-saving in terms of my own emotional and physical well-being. Only recently have I desired to have more community around and to share these things. Within the trauma and physical impairments that I’ve been dealing with, I’ve felt the need to have healing connected to my neopagan, earth-based spirituality as a way to be inside my body. I’ve been thinking about it as a somatic practice and that there must be people out there who yearn for that or who already have a connection to it who can help me deepen my practice as well. So, I've been branching out more.

“It’s only very recently that I’ve been allowing this into my work in an intentional way--though it might have bled in before--based on the disability that I’ve been experiencing, as a way to orient myself and be inside my body. Joanna is open to doing ritual with me as part of our rehearsal practice.

“I’m studying herbalism right now, and a lot it is just about taking your time. Sitting and being quiet. I’ve been allowing for time to unfold. The seedlings on the work started at New York Live Arts. Right now, we’re finding movement vocabulary and language around our rituals. Wearing this patch, it’s going to be navigating through a half-sightedness–a new element coming into it.”

History subtly streams through the work-in-progress that iele paloumpis is conjuring and exploring this fall.

“

my mother keening locates remnants of invisible trauma. The work explores various ways in which people heal themselves--through ritual and science and the magical nature of it all. Historically, acts of ‘healing’ or ‘fixing’ have often been used as forms of domination and control.

my mother keening reflects this duality and complexity. It is a ritual, a celebration, a humiliation, a lament for the dead.

“While Joanna and I are still working with ritual and healing, our current emphasis seems to be shifting. We're now looking at the many ways we try to escape pain but are ultimately still bound to it. And recently we're approaching this heavy subject matter somewhat lightly, in that we hope to make the absurdity of it all visible.

“We're trying to find the levity in always trying so hard, but ultimately always failing. At the same time we are not putting the emphasis on failure alone. There's been enough of that in queer art over that last decade.

“With all sincerity, we are striving for a different outcome--something like euphoria, bliss or hope.

"We'll see!”

*****

See a free showing of a work-in-progress by iele paloumpis with Jen McGinn and Joanna Groom on Monday, November 18, 8pm (on a bill with Germaul Barnes, Amapola Prada and Daniela Tenhamm-Tejos) at Movement Research's at Judson Memorial Church. For information, click

here.

iele paloumpis and Joanna Groom will also be showing

my mother keening on Friday, December 6 and Saturday, December 7, both at 8pm, at Brooklyn Arts Exchange (BAX), 421 5th Avenue, Brooklyn. For information, click

here.